The Final Shot at Survival

Five months ago, Sergeant H lost both his legs fighting in Gaza. An explosion in his tank instantly killed one crew member and left Sergeant H bleeding out. The next ten and a half minutes launched a journey of survival and rehabilitation that would test him far beyond the battlefield, redefining his strength and shaping the man who emerged on the other side.

Sitting straight-backed in his wheelchair, Sergeant H greets you with the confidence of someone who has already survived the unthinkable. Two weeks after receiving his new prosthetic legs, he is already planning the steps he will soon take on his own.

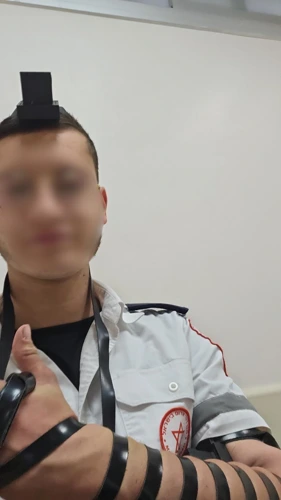

At just 20 years old, Sergeant H has already spent half a decade volunteering as a medic with Magen David Adom. Even during his army service, he refused to pause; after weeks away in the field, he would come home, swap his military uniform for his medic vest, and head straight into a night shift.

He was drafted into the army in March 2024, about five months after the war began, and joined the Armored Corps, the 7th Division. After completing seven months of training in southern Israel, Sergeant H moved up to Lebanon with the 82nd Brigade. By May 2025, he was on the front lines in Gaza.

“First we were in central Gaza, in Khan Yunis, and after two months we moved up to Shujaiya in northern Gaza. We entered Shujaiya, a neighborhood north of Gaza City, on July 1st. July 2nd was the day I was injured.”

For the entire night after entering the neighborhood, they were securing the area so that the infantry soldiers ahead of them could build a safe zone for the soldiers to stay in until their mission was complete. His team’s job was making sure there were no terrorists or threats in the area.

The Day of the Injury

“At about 8:30 a.m., we received a call on the communication system that an RPG had been fired at two infantry soldiers inside a house. We immediately drove toward them in our tank to cover their rescue so the evacuation teams could reach them. My position in the tank was the gunner—the one who aims, scans the area, and fires the cannon and machine gun. After about 500 meters of driving, within a minute, an IED exploded on our tank.”

At first, Sergeant H didn’t understand what was happening. “I screamed from pain, looked down, and saw that my left leg was on fire. I immediately threw myself backward from the gunner’s position toward the loader’s position.” He felt a thud behind him as his body flew back. When he turned to see the face of the force he had collided with, he was met with the still figure of a fellow comrade, killed instantly by the blast.

“I didn’t even have time to fully process it before realizing that my right leg had been completely amputated below the knee and that I was bleeding quickly. I saw my commander in the tank, badly burned from the torso up. His face, chest, and stomach were completely blackened, and his shirt had burned off.”

With the body of his friend beneath him, and his commander seriously injured, Sergeant H turned to the soldier in the driver’s position for help.

“I started shouting at him to call for rescue, terrified that because of the earlier RPG incident involving the infantry soldiers, no one would know what had happened to us. He started speaking over the radio. We couldn’t hear outside communications, but the command could hear us, so we just kept repeating that we were injured and needed help. No one knew exactly what was happening.”

Sergeant H’s commander had been thrown out of the tank and was lying unconscious on the turret. After about three minutes, he crawled back inside. Rescue teams had spotted him unconscious, lying on the outside of the tank, at which point it was understood something terrible had occurred there.

“I tried to put a tourniquet on myself but couldn’t because of the blood loss. I was conscious but had almost no strength left. It took ten and a half minutes before the rescue teams finally arrived.”

“Inside the tank, I was terrified. I knew I was bleeding out and had no idea what was happening outside—whether the other tanks or our platoon even knew what had happened to us. But because I was a medic, I knew I had to stay calm to slow the bleeding. I kept telling myself that under no circumstance could I lose consciousness. If I did, I wouldn’t make it.”

Even though he had practiced putting a tourniquet on himself dozens of times, Sergeant H wasn’t able to do it now when it mattered most. The shock and stress left his hands shaking and numb. “I wasn’t sure I would survive, but I still had a clear mind. I thought about my family, my girlfriend, and my friend who had been killed.”

“After about five minutes of screaming at the driver, I decided I needed to focus entirely on staying alive. I breathed slowly, taking shallow breaths. Only then did it hit me that my friend was gone. I turned and rested my head on his body because I needed something steady to prevent myself from losing consciousness. After a few minutes, I gathered the strength to lift myself just enough to look at him one last time, and I said a prayer for him and for myself. I said Shema Yisrael. I believed with all my heart that I would survive, even though I knew I was losing blood fast. Only once the rescue teams came did I truly believe I might make it.”

When the Brigade Commander regained consciousness and swung open the hatch of the tank, asking who was injured, Sergeant H answered immediately, his screams cutting through the chaos of the tank.

“He told me to come to him. I had one leg amputated and was still bleeding; my other leg was completely burned and shattered, blackened, and still smoking. I thought it had been amputated too—I had no idea it was still attached. But I had no room to argue. I began crawling toward him on my elbows until he saw me and pulled me out by my vest.”

Critical Condition and First Interventions

“The moment rescue arrived, I felt the greatest relief of my life. Those ten and a half minutes had felt like a year—a battle within myself to stay alive. Once they took over, I felt that my job was done and that now it was their turn.”

As the evacuation team sped toward the border, he slipped in and out of consciousness, crying out in pain each time he woke. At one moment of brief awareness, he found himself on the ground on the stretcher, the border in view and unfamiliar hands touching him as medics worked. Someone asked his name; he responded automatically, hardly conscious of anything beyond the question.

“Next thing I know, I’m waking up in the helicopter. I immediately yelled to the doctor, begging for ketamine so I could be put to sleep and stop feeling pain. He refused, explaining that I had lost too much blood and he didn’t want to risk making things worse,” but to Sergeant H, nothing could distract him from the excruciating pain.

Sergeant H’s case was so critical that the medics found themselves short of blood supply due to how much he required. They therefore made an emergency landing at a hospital in the south. “The last thing I remember is the helicopter doors opening and the doctor behind me saying, ‘Here, I’ll give you something.’ Then I woke up three days later.”

Recovery and Medical Setbacks

Much of his first week after the explosion is lost to sedation and surgeries. “I wasn’t shocked that my legs were gone,” he explained. “My family was really scared because they didn’t know if I knew what happened. They didn’t know if I would wake up and be in shock that I lost both my legs.”

A sudden medical crisis came next. A doctor noticed a developing aneurysm in his carotid artery, which pressed on his breathing tubes, preventing him from breathing. “They had to put me back into a coma. My vocal cords were damaged, and doctors told me they would never fully recover. I spoke in barely a whisper.”

The surgeons worked urgently: a tracheostomy to help him breathe, lines, tubes, and monitors across his body, and simultaneous efforts to stabilize both the aneurysm and the trauma to his legs. A stent was placed in his artery, blood thinners were started, and his blood pressure surged dangerously.

“But three weeks later, during a follow-up, they saw that my vocal cords had begun moving again, something they couldn’t explain. I was told I would be able to recover with therapy. I truly feel it was a miracle that I can speak normally now.”

But as one crisis resolved, another began, and doctors found yet another danger—fungal infections deep in his legs, destroying flesh and creeping toward bone. “They thought maybe they would have to amputate above my knee,” he recalled. It was only because a doctor happened to notice a spreading black spot that they caught it in time. He was rushed to Rambam Hospital in the north for hyperbaric treatments, ten sessions inside a pressure chamber meant to kill the fungus before it killed him.

Four weeks after the injury, after moving between ICUs and surgical units, he finally entered the phase that resembled recovery. Back at Sheba Hospital, medical teams removed tubes and needles, began easing him off pain medications, and reintroduced the simple act of eating and drinking after a month of surviving on a feeding tube.

In rehabilitation, they worked on everything the injury had stripped away—his strength, his mobility, and, as he put it, “my nefesh—my spirit, my mental state.”

“Slowly, I got back to myself,” he said. Just two weeks ago, he received his prosthetics and took his first steps with them. “And I’m making amazing progress.”

“Throughout the whole time, I believed in the miracle that happened to me. Even though I lost my legs and felt devastated knowing I would be disabled for the rest of my life, I was grateful that my head wasn’t injured, my arms were fine, and my internal organs weren’t damaged. I was still myself. That gratitude helped me keep a positive attitude.”

“There were several moments that felt miraculous. First was simply making it onto the helicopter alive. Later, I met the unit that treated me in the field, and they told me that I had been on my last heartbeats and that if I had waited another minute and a half before receiving blood, I wouldn’t have made it. Surviving with no injuries other than my legs also feels like a miracle.”

Moving Forward Post Injury

Sergeant H was determined to keep optimistic, always laughing with the medical staff. “I asked them questions because I love medicine and wanted to understand everything they were doing, even if it was to my own body.”

“Throughout recovery, I joked with the nurses and doctors and tried to stay positive. I also felt the presence of my friend in the tank with me, who died. I felt his smile with me throughout the journey, in moments of progress and moments of difficulty, as if he were holding me up.”

What lingers with him most is the sheer courage of his team inside that tank. The driver, paralyzed by fear at first, forced himself to keep talking over the radio. The commander, burned and barely conscious, tried to do the same. And Sergeant H, losing blood by the second, drove the driver to keep fighting. The knowledge that every member of the crew held on, that no one surrendered to panic, became a powerful anchor in his recovery.

“Since then, I’ve learned to appreciate the small things: getting dressed, eating, drinking, showering, standing up, doing things independently—even simply breathing. All these things I had taken for granted, and suddenly I understood how precious they are.”

“So this Hanukkah, the light I’m carrying forward is a positive attitude. Even when everything feels dark and endless, I choose to see the best in what’s happening. I look forward to it. I believe that things will be okay. Not everything that happens is good, but in the end, things will turn out alright. As long as I can keep a smile on my face and stay positive, everything will be okay.”